It seems likely that we are in a renaissance for futures thinking. There is more genuine interest, widespread and general, in futures and foresight work than at any point during the ten-plus years in which I’ve had direct experience in the field. No doubt the volatility and uncertainty over the past two-plus years, through COVID and a myriad of other unpredictable — but not unimaginable — events has had an impact on the perspectives of decision-makers.

This newfound interest in foresight is a positive development but it brings with it a core challenge, especially for those undertaking foresight projects with little past experience, which is when and how to actually use foresight.

As foresight practitioners, we must consider how and when to best use foresight, so as not to — in our well-intentioned push to incorporate foresight into our work and decision-making — create a mismatch in what organizations want vs. what they need; in what their expectations are vs. what we can accomplish; and what their ambitions are vs. what they can actually accept. Intentional or not, foresight projects are often asked to do things they cannot or should not do, leading to projects that fall flat or “fail.” The resulting skepticism about futures thinking as a whole does more harm than good; thus where and how we decide to deploy foresight is equally important to the work we do.

Or more simply, while all strategic projects should somehow be infused with foresight, not all projects need to be foresight projects.

What exactly does this mean, in practice? How do we address those mismatches that we can unwittingly create? How do we more effectively deploy foresight where it can make the greatest difference?

For me, I like to start by addressing those potential mismatches head on anytime I’m scoping a project out. I ask: “What is the actual impact we can make? What decisions are we hoping to influence – if any? What outcomes are aspirational, and what outcomes are necessary?” Being painfully realistic about these answers is key, especially when our stakeholders may not have the experience needed to properly set expectations.

For us as practitioners, these answers will help us to properly scope our projects. We need to remain hyper-focused on the influence the project should have, if we want to ensure that our foresight work is effective, impactful, and successful. Although it’s wonderful when projects can be scoped to cover everything in one go, in reality that is fairly rare. More commonly, projects have limited budgets, limited scope, and if we’re honest, limited impact. It’s incumbent on us to make sure that we adjust our work and efforts to realistically maximize the impact we can have – which means focusing our projects more tightly.

So, How Do We Decide What to Do?

One way I like to think about how to differentiate between types of projects is to consider if the work will be centered around content, or around capacity. In other words, will the creation and sharing of foresight content be what drives the project forward and help define success, or will the capacity of teams to utilize foresight in order to drive strategy and tactics be central to success?

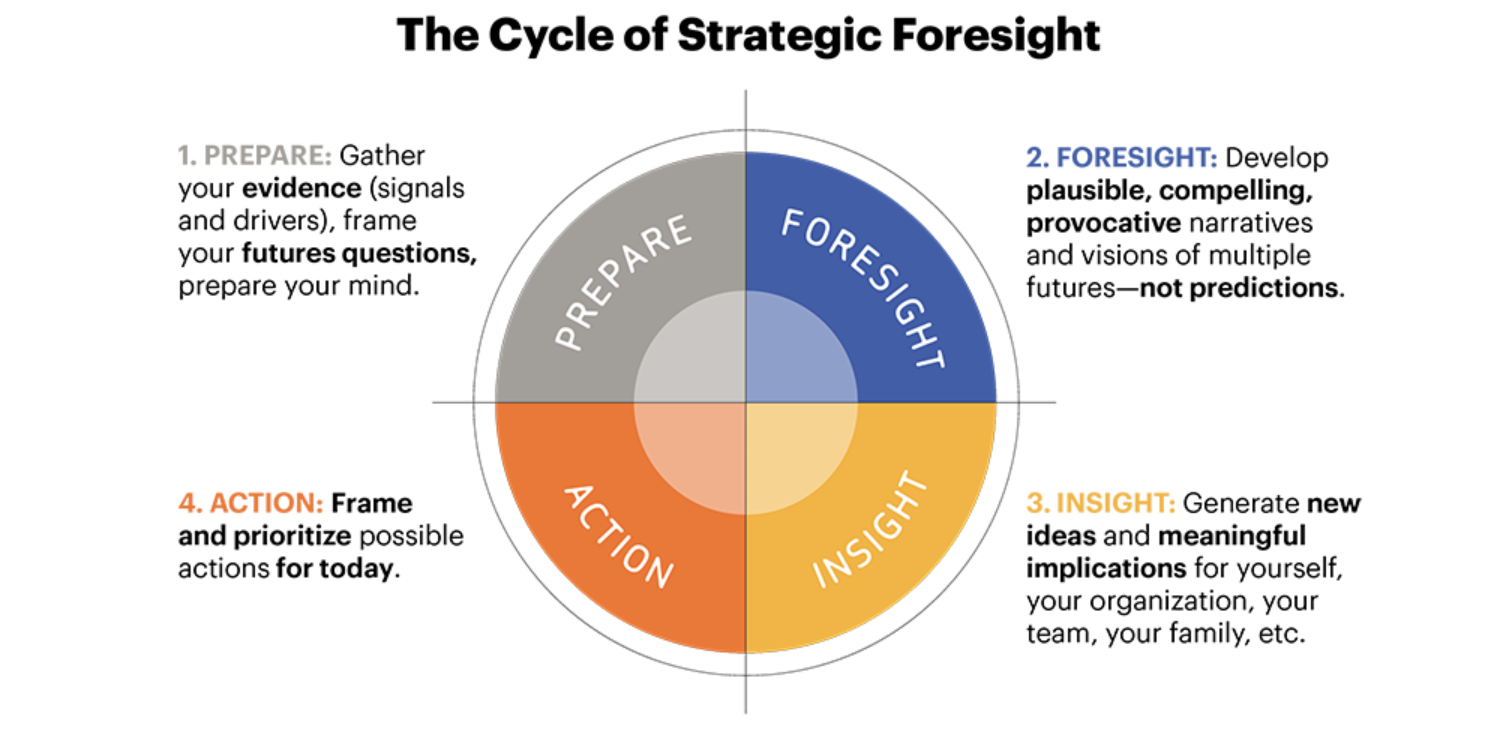

In the Institute’s Prepare-Foresight-Insight-Action cycle (see below), this roughly corresponds to a break between the top of the circle and the bottom of the circle. Content projects will focus more on the Prepare and Foresight parts of the cycle, while Capacity projects will require more time in Insight and Action.

Centering Content

In the first case of centering around content, the bulk of effort in a project should go towards crafting plausible and provocative forecasts. Obviously, there will be a lot of time and effort allocated towards developing scenarios, narratives, forces, or other forms of forecasts that will inspire people to think differently. But equally importantly, because the foresight developed will need to survive scrutiny and skepticism, these projects will require sufficient effort to gather the building blocks that underpin your foresight – doing the horizon scanning, expert interviews and workshops, and primary research (when applicable).

It also means putting in the time to adequately prepare your team and stakeholders to engage with your foresight. Exercises like “Look Back to Look Forward” or “Frame Future Conversations,” from the IFTF Foresight Essentials Toolkit, can be great ways to bring stakeholders along without requiring too much time investment.

For content projects, the end deliverables will often take the form of some sort of share-out or experience built around your foresight. At the Institute, many of our past Maps of the Decade are great examples of what a content-centric project looks like.

A more immersive example, complete with physical experiences in the real world, can be seen in the Hawaii in 2050 project by Dr. Jake Dunagan and Dr. Stuart Candy.

Centering Capacity

In the second case of centering around capacity, the value does not come from the foresight content as much as it does from the ability of your team to harness the insights and provocations that come from foresight. In other words, these projects are focused on building or tapping into an organization’s capacity to utilize foresight to promote transformative action.

In practice, this often means that while these projects will take foresight as inputs into workshops, strategy meetings, or planning sessions, the bar for foresight is lower than in a content project. I would argue that in these projects, “good enough” foresight is good enough. Instead, the important work is to help stakeholders internalize lessons from that foresight, challenge their existing assumptions, and more confidently make decisions with a long-term perspective in place. Investment into creating the space needed to bring teams together, foster collective exploration and immersion, and have the conversations that can yield insights and realizations is critical.

Although it is harder to point to public examples of this type of work, it is not hard to describe. Consider innovation-focused projects where facilitators are putting foresight inputs in front of non-foresight practitioners and asking them to find new whitespaces or business models to consider. Or an organizational strategy project that is considering how to structure a company for the future of work. These could both be more “capacity-centric” projects where foresight is a key input, but participants might not have practical experience with foresight content.

***

There is a lot that goes into scoping a foresight project well. Not only are there many types of foresight projects, there are many approaches. Thinking through where the center of gravity for your project should be — content or capacity — can be a good starting point as you begin to plot out your efforts and hone in on the activities that will result in the greatest impact. In the end, it’s worth the time and effort. Not only will a well-scoped project be more likely to succeed, it will be more likely to build goodwill and confidence throughout the organization for the type of work that we want to do. Remember, building a futures thinking mindset takes time. We can’t rush it, nor should we.

Want to receive free tips, tools, and advice for your foresight practice from the world's leading futures organization? Subscribe to the IFTF Foresight Essentials newsletter to get monthly updates delivered straight to your inbox.

Ready to become a professional futurist? Learn future-ready skills by enrolling in an IFTF Foresight Essentials training based on 50+ years of time-tested and proven foresight tools and methods today. Learn more ».